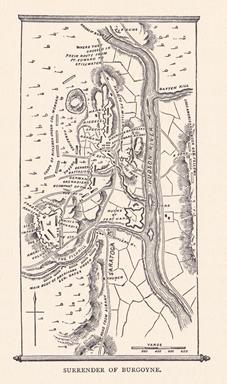

Saratoga, October 11th to 16th, 1777

As found in the book, "The Hessians The Revolution", By Edward J. Lowell.

CHAPTER XIV.

SARATOGA, OCTOBER 11TH TO 16TH, 1777.

At the camp north of the Fishkill Burgoyne halted, and never resumed his march. Lieutenant-colonel Southerland was sent forward to build a bridge across the Hudson near Fort Edward, but was presently recalled. At daybreak on the i ith a brigade of Americans made a dash across the Fishkill, seized all the boats and much of the stores, took a few prisoners, and retreated before a brisk fire of grape-shot. All day long the English army was cannonaded from front and rear.

In the evening General Burgoyne summoned Generals Riedesel and Phillips to consult with him on the situation of the army. Burgoyne himself held it impossible to attack the enemy, or to maintain his own position if attacked in the centre or on the right wing. General Riedesel thereupon proposed to retreat in the night, abandoning the baggage, fording the Hudson four miles below Fort Edward, and making through the woods for Fort George. No decision was reached, however.

Another council was held on the following afternoon, two brigadier-generals being admitted to it. General Riedesel insisted on his plan of the day before, “very emphatically, and with hard words,” and the plan was agreed to. As it appeared that rations had not been given out to the troops, the movement was postponed until late in the evening. At ten o’clock Riedesel sent word to Burgoyne that all was ready, but was answered that it was too late to undertake anything. Thus was the last chance thrown away, for on the next morning the army was completely surrounded.

On the 13th of October a third council of war was called, including the regimental commanders. General Burgoyne explained the hopelessness of the situation. Only five days’ provisions were left. The whole of the British camp could be reached by the American grape-shot and rifle bullets. Gates’s army was drawn up behind a marshy ravine, so far from the Hudson that if Burgoyne were to move out to attack it the Americans could cross the river and take him in the rear. Even should the enemy be successfully attacked and defeated there were not enough provisions remaining for the march to Fort George. The position in which the army now stood could not be defended in the centre or on the right wing. (This was the part of the ground principally occupied by the Germans.)

Burgoyne declared that no one but himself was responsible for the situation of the army, as he had asked no advice and only expected obedience. Riedesel thanked Burgoyne for his declaration, which made it clear to all that he (Riedesel) had had no share in planning the movements of the army, and he called on the English officers present to bear witness to this, if ever he were called to account.

Burgoyne then laid the following questions before the council:

1st. Whether there were examples in the history of war that an army in this condition had capitulated.

2d. Whether in such a condition a capitulation were dishonorable.

3d. If this army were really in a condition where it must capitulate.

To the first question all answered that the condition of the Saxon army near Pirna, of General Fink near Maxen, and of Prince Maurice of Saxony, had not been so bad nor so helpless as that in which this army now was; and that nobody had been able to blame the generals who had capitulated under such circumstances in order to save their armies; only that the King of Prussia had cashiered General Fink; but that was done from personal disfavor.

To the second question all, answered that for the reasons above given the capitulation could not be dishonorable. And as to the third question, all were agreed that if General Burgoyne saw the possibility of attacking the enemy they were ready to sacrifice their blood and their lives; but if this were not feasible they held it better to save the troops for the king, by an honorable capitulation, than to hold out .longer and run the danger of having to surrender at discretion after exhausting all their provisions, or to be attacked in their bad position and scattered, and then destroyed in detail.

General Burgoyne thereupon produced the draft of a capitulation, the terms of which seemed favorable, and were unanimously approved of by his officers. A drummer was then sent over to the American camp to announce that on the next day a staff officer would be sent to discuss matters of importance with General Gates; and to ask for a truce in the meanwhile. This General Gates granted.

About ten o’clock in the morning of the 14th of October Colonel Kingston was sent over to the American camp with Burgoyne’s proposals, w’hich were in substance that his army should yield themselves prisoners of war, but under condition that they should be taken to Boston and thence shipped to England, agreeing not to serve against the Americans during the war, unless previously exchanged.

General Gates did not accept these proposals, but drew up another form of capitulation, in six articles, setting forth that “General Burgoyne’s army being reduced by repeated defeats, by desertion, sickness, etc., their provisions exhausted, their military horses, tents, and baggage taken or destroyed, their retreat cut off, and their camp invested, they can only be allowed to surrender as prisoners of war.”

The sixth article provided that “these terms being agreed to and signed, the troops under his Excellency’s, General Burgoyne’s command, may be drawn up in their encampments, where they will be ordered to ground their arms, and may thereupon be marched to the river side on their way to Bennington.” [Footnote: De Fonbianque’s “Burgoyne,” pp. 306, 307.]

General Burgoyne hereupon called the council of war together and read them the above proposals. The officers declared unanimously that they would rather die of hunger than accept such dishonorable terms. Colonel Kingston was sent back to tell General Gates that if he did not mean to recede from the sixth article, the negotiations must end at once; the army would to a man proceed to any act of desperation sooner than submit to that article. Hereupon the truce came to a close.

Every one in the army was astonished when new proposals were received from General Gates on the following morning (October 15th, 1777). The terms asked for by Burgoyne were substantially granted, but it was stipulated that the conquered army should leave its position by two o’clock on the same day.[Footnote: Gates was undoubtedly influenced by news of Vaughan’s expedition up the Hudson.]

This sudden change excited the suspicion of the English and German officers. The council of war determined to accept Gates’s proposal, but to try to gain time. Commissioners were appointed on both sides, and the discussion of details continued until eleven o’clock at night. The Americans granted all that was demanded of them. The Englishmen on their side promised that General Burgoyne should sign the articles and send them to General Gates in the morning. The truce was to continue.

On the same night a deserter came in and announced that there was a rumor that Sir Henry Clinton had not only taken the forts in the Highlands, but had advanced a week ago to Esopus, and was probably at Albany by this time. Burgoyne and some of his officers were so much encouraged by this news that they were strongly tempted to refuse to surrender. The council of war was called together to answer the following questions:

1st. Whether a treaty finally arranged by commissioners with full powers, which the general had promised to sign as soon as commissioners should have removed all difficulties, could honorably be broken?

2d. Whether the news received was sufficiently certain to be a motive for breaking off an agreement which, considering the position, was so favorable? and

3d. Whether the army was in sufficiently good spirits to defend its present position to the last man?

On the first of these questions fourteen officers, against eight, were of opinion that the agreement could not honorably be broken off. As to the second, opinions were divided. Those who answered in the negative argued that the deserter was speaking only from hearsay, and that even if Sir Henry Clinton were at Esopus, the distance thence was so great that his approach could not help the army in its present condition. To the third question all officers from the left wing answered in the affirmative, but those from the centre and right said that although their soldiers would fight with great valor if led against the enemy, yet they were so well aware of the weakness of their position, that they might not do as well if attacked. As the Brunswick troops principally occupied the centre and right of the line, it is to this declaration of their officers that Burgoyne probably refers when he speaks in a private letter of “the Germans dispirited, and ready to club their arms at the first fire.” [Footnote: Dc Fonbianque’s “Burgoyne,” p. 315.]

Still hoping to gain time, Burgoyne tried one pretext more. He wrote on the morning of the i6th to General Gates, saying that he had heard from deserters that that general had sent off a considerable part of his army to Albany during the negotiations; that this was contrary to good faith, and that he, Burgoyne, would not sign the capitulation until an officer of his staff should have inspected the American army to assure himself that it was three or four times as large as the English. Gates seems at last to have grown tired of this fooling. He sent back word that his army was quite as strong as it had been, and had moreover received reinforcements; that he held it neither politic nor for his honor, to show his army to one of General Burgoyne’s officers; and that that general had better think twice what he did, before breaking his word, as he would be held responsible for the consequences. Gates added that he was ready to show General Burgoyne his whole army as soon as the articles of capitulation should be signed, and he assured him that it was four times as large as the British, without counting that part of it which was beyond the Hudson. He was unwilling, however, to wait more than an hour for an answer, and at the end of that time should be forced to take the most severe measures.

The council was summoned for the last time, and no one was found to advise the general to break his word. Burgoyne called Phillips and Riedesel aside and begged for their friendly counsel. Both were silent for a time, and then Riedesel explained that if Burgoyne were held responsible in England, it could only be for the movements that had brought the army into such a position, and perhaps for first undertaking a capitulation, and because he had not retreated in time to be master of the line of communications with Fort George. But now, after all the steps that had been taken, Riedesel held it much more dangerous to break the agreement, on the strength of an uncertain and untrustworthy rumor.

Brigadier-general Hamilton, who came up and was asked his opinion, agreed with Riedesel. General Phillips only said that things had come to such a pass that he had no advice nor help to give. Burgoyne, after much vacillation, determined to sign, and the articles in due form were sent to General Gates.[Footnote: The above description of the negotiations for the surrender is taken principally from Baroness Riedesel’s book, in which is given an extract from a military memoir dated Stillwater, October t8th, 1777, and signed by several of the principal German officers. See also, concerning this memoir, Eelking’s “Riedesel,” vol. H. pp. 210, 211.]

In the surrender five thousand seven hundred and ninety-one men were included. It is stated by Riedesel that not more than four thousand of these were fit for duty. The number of Germans surrendering is set down by Eelking at two thousand four hundred and thirty-one men, and of Germans killed, wounded, and missing down to October 6, at one thousand one hundred and twenty-two.[Footnote: It will be noticed that the time from October 6th to October x6th, during which there was a good deal of fighting, is omitted from the above estimate. See Eelking’s “Hülfstruppen,” vol. i. pp. 321, 322; “Riedesel,” vol. ii. p. 188.] The total loss of the British and their mercenaries, in killed, wounded, prisoners, and deserters, during the campaign, including those lost in St. Leger’s expedition to the Mohawk and those who surrendered on terms at Saratoga, was not far from nine thousand.

The days that preceded the surrender had been days of confusion. Baroness Riedesel says that on the evening of the gth of October, in Saratoga, when they had marched but half an hour during the day, she asked Major-general Phillips why they were not moving on while it was yet time. The general admired her resolution and wished she were in command of the army. The same lady relates that Burgoyne spent half of that critical night in drinking and making merry with his mistress.

The army was given over to misery and disorder. On the ioth the baroness fed more than thirty officers from her private stores, “for we had a cook,” says she, “who, although a great scoundrel, was equal to every emergency, and would often cross little rivers in the night and steal mutton, chickens, or pigs from the country people, which he afterwards made us pay roundly for, as we subsequently learned.” [Footnote: Baroness Riedesel, p. 178.] These supplies were at last exhausted, and the lady, in her indignation, called on the adjutant-general, who happened to come in her way, to report to Burgoyne the destitution of officers wounded in the service. The commander-in-chief took this in good part, came to her in person, thanked her for reminding him of his duty, and gave orders that provisions should be distributed.’ The baroness believed that Burgoyne never in his heart forgave her interference. It seems to me, from the writings of both, that spite lay rather in her bosom and her husband’s than in that of Burgoyne. The memorandum which General Riedesel wrote and caused to be signed by his officers immediately after the surrender is a long impeachment of Burgoyne, and sets forth the evil consequences of his not consulting the writer, or of not executing the latter’s plans promptly. It is clear that Riedesel held Burgoyne responsible for the misfortunes of the army, misfortunes which he himself took so deeply to heart that his health and spirits were for a long time seriously affected. Before leaving America, in the spring of 1778, Burgoyne wrote to the Duke of Brunswick, praising Riedesel’s intelligence and the manner in which he had executed the orders of his superior officer.[Footnote: De Fonblanque’s “Burgoyne,” p. 335. See also Riedesel’s order to the German troops expressing Burgoyne’s satisfaction with them.—EeI. king’s “Hiilfstruppen,” vol. i. p. 341.] Upon this Riedesel wrote a most friendly letter to Burgoyne, thanking him in his own name and that of his officers for the kindness which the commanding general had shown to them. “If good fortune did not crown your labors,” he continues, “we know well that it was not your fault, and that this army was the victim of the reverses of war.” This solitary expression of confidence is not to be reconciled with what Riedesel says at other times and in other places. The military memorandum above-mentioned, published in the baroness’s book, is sufficient proof of this. In the same spirit are conceived Riedesel’s comments on Burgoyne’s report of the campaign. These comments, which were addressed to the Duke of Brunswick and his countrymen, are dated Cambridge, April 8th, 1778, a little more than a month later than the letter above quoted. They complain explicitly that General Burgoyne, while speaking highly of Riedesel himself, passes lightly over the services of his troops. The German general’s complaints in this respect are but slightly justified by Burgoyne’s report.[Footnote: Eelking’s “Riedesel,” vol. ii. pp. 193—210. I do not make out whether these comments were actually sent to the Duke of Brunswick or were found by Eelking among Riedesel’s private papers.]

But we must return to the baroness. On the afternoon of the ioth of October the Americans began to fire again on the British army. “My husband sent me word,” she writes, “to go at once to a house which was not far off. I got into the carriage with my children. We were just coming up to the house when I saw five or six men with guns on the other side of the Hudson River, aiming at us. Almost involuntarily I threw the children into the bottom of the carriage, and myself over them. At the same moment the fellows fired and shattered the arm of a poor English soldier behind me, who was already wounded, and was also retiring into the house. No sooner had we arrived than a terrible cannonade began, which was principally directed against the house where we had sought shelter; probably because the enemy had seen a great many people go in and thought the generals must be there. Alas! it was only women and wounded men. We were at last compelled to take refuge in a cellar, where I placed myself in a corner near the door. My children lay on the ground with their heads in my lap. Thus we spent the whole night. A horrible smell, the crying of the children, and, more than all these, my anxiety, prevented my closing my eyes.

“Next morning the cannonade began again, but from another side. I advised everybody to go out of the cellar, and undertook to have it cleaned, as other- wise we should all be sick. My advice was followed, and I set many hands to work, which was very necessary, as there was much to do. . . . When everything had been cleared out, I considered our place of refuge; there were three fine cellars, well vaulted. I proposed that the most dangerously wounded officers should be put into one, the women in the second, and all other persons in the third, which was nearest the door.

“I had had the place well swept out and disinfected with vinegar, and we were all beginning to get into our proper places, when the firing began again terribly, and created great alarm. Several people who had no right to come in threw themselves towards the door. My children had already gone down the cellar stairs, and we might all have been smothered, had not God given me strength to place myself before the door and bar the entrance with outstretched arms; otherwise some of us would certainly have been injured. Eleven cannon balls went through the house, and we could clearly hear them rolling away above our heads. One poor soldier had been laid on the table to have his leg taken off, when a cannon ball came and carried away the other. His comrades had all run away, and when they came back to him they found him in a corner of the room, whither he had rolled himself in his fear, and hardly breathing. I was more dead than alive, but not so much on account of our own danger as for that in which my husband was, who yet often sent to ask how we were getting on, and sent me word that he was well.

“Major Harnich and his wife, a Madame Rennels, who had already lost her husband, the wife of the good lieutenant who had shared his broth so kindly with me the day before, the wife of the commissary, and I were the only ladies with the army.[Footnote: Sic. This list is intended to include the ladies, not the women, whose numbers I have no data for ascertaining. The Baroness had two female servants. A soldier’s wife is spoken of later. The proper names above should be Harnage and Reynell, but all German writers during this war are very careless as to the spelling of proper names.] We were sitting together and bewailing our sad fate, when some one came in, and people whispered in each other’s ears and looked sadly at each other. I noticed this, and that they were glancing at me, without saying anything more to me. This gave me a frightful idea that my husband had fallen. I screamed; but they assured me that this was not the case, and made signs to me that it was the poor lieutenant’s wife whose husband had met with this misfortune. She was called out a moment later. Her husband was not yet dead, but a cannon ball had taken off his arm at the shoulder. We heard his moans all night, echoing horribly through the vaults of the cellar, and the poor man died towards morning. Otherwise this night was like the last. Meanwhile my husband came to see me, which soothed my trouble and gave me back my courage.

“The next morning we began to get into a little better order. Major Harnich and his wife and Madame Rennels made themselves a little room, shut off with curtains, in one corner. It was proposed to me to have another corner arranged in the same way, but I preferred to remain near the door, so that I could get out quicker in case of fire. I had a heap of straw brought, laid my beds on it, and slept there with my children. My women slept near us. Opposite were the quarters of three English officers, who were wounded, but yet were resolved not to stay behind in case of a retreat. One of them was a Captain Green, aid to General Phillips, a very estimable and well-bred man. All three swore to me that in case of a hasty retreat they would not abandon me, and that each of them would take one of my children on his horse. One of my husband’s horses always stood ready saddled for me. My husband was often minded to send me to the Americans, in order to get me out of danger. I represented to him that it would be worse than all that I now had to suffer, to be with people whom I should have to meet with forbearance while my husband was fighting against them. He, therefore, promised me that I should continue to follow the army. Yet I often became anxious in the night lest he might have marched away, and crept out of my cellar to look, and when I had seen the soldiers lying about the fires in the cold night, I could sleep more quietly.

“The things that had been intrusted to me caused me great anxiety.[Footnote: Money and valuables belonging to various officers.] I had them all in the front of my corsets, because I was so afraid of losing some of them, and I made up my mind not to meddle with such things in future. On the third day I got the first opportunity to change my linen, for they had the kindness to clear a corner for me for the purpose; meanwhile my three officers above mentioned stood sentinel not far off. One of these gentlemen could imitate the lowing of a cow and the bleating of a calf very naturally; and when my little daughter Fritzchen cried in the night,,he made the noises for her, which quieted her and made us laugh.

“Our cook procured us food, but we had no water, and I was often obliged to drink wine to quench my thirst, and also to give it to the children. It was almost the only thing that my husband took; which at last made our faithful chasseur Rockel anxious, so that he said to me one day: ‘I fear that the general is disgusted with life, from apprehension of becoming a prisoner; he drinks so much wine.’ The continual danger to which my husband was exposed kept me in constant anxiety. I was the only one of all the women whose husband had not been killed or met with some misfortune; and so I often said to myself: ‘Shall I be the only fortunate one?’ especially as my husband was exposed to so much danger, day and night. He never passed the night in a tent, but always lay in the open air by a watch-fire. That alone might have caused his death, as the nights were so cold and damp.

“Our need of water was so great that at last we found a soldier’s wife who had the courage to bring some from the river; which no man was willing any longer to undertake, because the enemy shot all those that went to the river through the head. They let the woman alone, out of respect to the sex, as they afterwards told us.

“I tried to distract my thoughts by busying myself with our wounded. I made them tea and coffee, for which I received a thousand blessings. I often shared my dinner with them. One day a Canadian officer came into our cellar hardly able to stand. We at last got it out of him that he was almost dying of hunger. I was very happy to be able to offer him my food, which brought back his strength and won me his friendship. When we afterwards returned to Canada, I made the acquaintance of his family. One of our greatest troubles was the smell of the wounds when they began to fester.

“Once I undertook the cure of Major Plumfield, aide-de-camp to General Phillips. A small musket- ball had gone through both his cheeks, shattered his teeth and grazed his tongue. He could not keep anything in his mouth; the matter almost choked him, and he could take no nourishment but a little broth, or something fluid. We had Rhine wine. I gave him a bottle, in hopes that the acid of the wine would cleanse his wound. He constantly took a little in his mouth, and that alone did such good service that he was healed, by which I gained another friend. And thus, in the midst of my hours of trouble and sorrow, I had moments of pleasure that made me very happy.

“On one of these sad days General Phillips wished to visit me and accompanied my husband, who used to come once or twice every day at the peril of his life. He saw our situation, and heard me entreat my husband not to leave me behind, in case of a hasty retreat. He, himself, supported my cause, when he saw my great repugnance to being in the hands of the Americans. On going away he said to my husband: ‘No! I would not come here again for ten thousand guineas; for my heart is quite, quite broken.’

“Meanwhile, all who were with us did not deserve pity. There were also cowards among them, who stayed in the cellar for nothing, and afterwards, when we were prisoners, could take their places in the ranks and go on parade. We stayed six days in this hornble place. At last they spoke of surrender, for they had delayed too long, and our retreat was cut off. A truce was made, and my husband, who was quite worn out, could come into the house, and go to bed again, for the first time in a long while. Not to disturb his sleep, I had had a good bed made for him in a little room, and I lay down to sleep with my children and my two women in a hall near by. But about one o’clock in the night somebody came and wanted to speak to him. Greatly against my will, I was obliged to wake him up. I noticed that the message was not pleasant to him; that he immediately sent off the man to headquarters, and then lay sullenly down again. Presently afterwards, General Burgoyne had all the other generals and staff officers called to a council of war, to be held early in the morning. In this council he proposed, on the strength of false news which he had received, to break the capitulation which had already been made with the enemy. It was at last decided, however, that this was neither feasible nor advisable; and this was lucky for us, for the Americans told us later that if we had broken the capitulation we should all have been massacred, which they could easily have done, as we were not over four or five thousand strong, and had given them time to bring together more than twenty thousand men.

“On the morning of the i6th of October my husband had to go to his post again, and I into my cellar.

“On this day the officers, who had hitherto received only salt meat, which was very bad for the wounds of those who were hurt, had a great deal of fresh meat divided among them. The good woman who had always brought us water made an excellent soup of it. I had lost all my appetite, and during the whole time had taken nothing but a crust of bread soaked in wine. The wounded officers, my companions in misfortune, cut off the best piece of beef, and presented it to me with a plate of soup. I told them that I was unable to eat anything; but as they saw that it was necessary for me to take some nourishment, they declared that they would not touch a morsel themselves, until I had given them the pleasure of seeing me take some. I could no longer withstand their kind entreaties; whereupon they assured me that it made them very happy to be able to offer me the first good thing they had had.

“On the 17th of October the capitulation was effected. The generals went over to the American General Gates, and the troops laid down their arms and surrendered themselves prisoners of war. And now the good woman who, with danger to her life, had brought us water, received the reward of her services. Every one threw whole handfuls of money into her apron, and altogether she received more than twenty guineas. At such moments the heart seems open to feelings of gratitude.” [Footnote: Baroness Riedesel, pp. 580—591.]

[ The Hessians In The Revolution ]