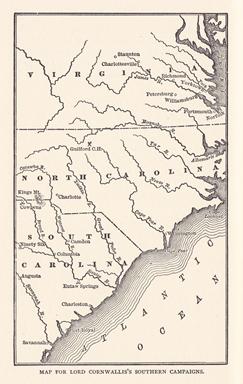

The Southern Campaign of 1781

As found in the book, "The Hessians The Revolution", By Edward J. Lowell.

CHAPTER XXIII.

THE SOUTHERN CAMPAIGN OF 1781.

When Sir Henry Clinton sailed away from Charleston in June, 178o, two Hessian regiments were included in the garrison which he left behind him, and one more such regiment was brought from Savannah soon afterwards. I do not find any record of an active part taken by these regiments in the campaigns which Lord Cornwajljs conducted in South and North Carolina. On the x6th of August, 1780, the American army under General Gates was routed at Camden, and on the i8th Tarleton surprised a party under Sumter. Six weeks later the tables were partially turned by the brilliant engagement at King’s Mountain, where about fourteen hundred backwoodsmen surrounded and stormed a hill held by an equal number of British regulars and Provincials, killing and wounding two fifths of them, and taking the remainder prisoners.

In the month of October, 1780, General Leslie, with several English regiments, the Hessian Regiment von Bose, and a detachment of one hundred chasseurs left New York for the Southern States. They landed at Portsmouth, in Virginia, but shortly afterwards abandoned this post and proceeded to Charleston, where they arrived in the latter part of the year.

Having this reinforcement within reach, Lord Cornwallis started from Wynesborough, west of Camden, and marched against General Greene, who, at Washington’s desire, had been appointed Gates’s successor. The British army numbered about thirty-five hundred. Learning that Morgan, with a separate force,[Footnote: Morgan had from eight hundred to one thousand men.] was on the south side of Broad River, Cornwallis determined to cut him off from Greene’s main army. For this purpose he detached Lieutenant.colonel Tarleton, with about a thousand men. Tarleton was to attack Morgan in front, while Cornwallis was to follow up the left bank of Broad River and capture the fugitive Americans. Tarleton came up with Morgan on the morning of the 17th of January, 1781. Hardly waiting to form his army, the gallant cavalry colonel rushed on his despised enemy. The American militia forming the first line gave way. The second line, formed largely of Continentals, stood firm. Tarleton ordered up his reserves. The Americans gave ground, then turned and poured in a vigorous and well-directed fire. This unexpected resistance threw the British into confusion. They wavered. Two companies of Virginia militia charged with the bayonet. The British gave way on all sides. Tarleton rallied about fifty horsemen, and, for a moment, checked the pursuit. Most of the British infantry were taken, but the cavalry escaped, and the baggage was destroyed. The Americans took about five hundred prisoners, and about a hundred Englishmen were killed. The American loss did not exceed seventy - five. Two standards, two cannon, thirty-five wagons, eight hundred muskets, and one hundred horses fell into Morgan’s hands. The cannon had already been captured by Gates at Saratoga and by Cornwallis at Camden. Morgan’s battle, fought almost in the wilderness, is called Cowpens, after the place where the inhabitants of that part of the country collected and salted their roving cattle.

Soon after his victory General Morgan was laid up with rheumatism and forced to leave the army.[Footnote: Lee, however, blames Morgan for leaving the army at this time.— “Memoirs,” pp. 237, 583.] Few men engaged in the Revolutionary War had done better service to their country. There is a legend which tells that the house he built for himself near Winchester, in the Valley of Virginia, was constructed of stones quarried by Hessian prisoners, who carried them for miles on their shoulders. The story is picturesque and not impossible, but I know of no German authority for it.

Cornwallis was disappointed but not daunted by the rout of his ablest subordinate, and of nearly a third of his soldiers. On the day after the battle of Cow- pens he was joined by Leslie’s division. In a few days he was marching across North Carolina, and Greene was retreating before him. The latter was driven out of the state and across the Dan River. Cornwallis called on the Tories to rise, and these at first showed an inclination to do so, but a party of them was attacked and dispersed by a superior force under Henry Lee and Pickens, and the others became discouraged and went home again.

At last General Greene, having received reinforcements, advanced again to Guildford Court House, in North Carolina, and prepared to give battle. His army consisted of sixteen hundred and fifty-one Continentals and more than two thousand militia. Lord Cornwallis commanded eighteen hundred and seventy- five veterans. On the 15th of March, 1781, Greene drew up his army in three lines. The foremost of these was composed of North Carolina militia, posted in the woods behind a fence. A portion of this line was on the edge of a clearing. Its left was supported by a body of riflemen under Lieutenant-colonel Henry Lee and Colonel Campbell. Greene’s second line, stationed three hundred yards behind the first, was composed of Virginia militia. They stood in the thick woods. The third line contained all the Continentals of the army.

Opposite to this force, after a skirmish of the advanced-guards, Lord Cornwallis drew up his army in two divisions. The left wing was under Lieutenant- colonel Webster, the right under Brigadier-general Leslie. The right wing first came on the North Carolina militia, which fled at its approach. Lee and Campbell, however, with their riflemen, continued in action. The British advanced against the Virginia militia. The whole English line was now engaged, and the Virginians defended themselves so well that Lord Cornwallis was obliged to call up his reserves. The American second line was finally driven back, and the British pressed forward to meet the Continentals. By this time a good deal of confusion had been caused among the English, fighting in the thick woods. It was Lieutenant-colonel Webster,with his brigade, who first met the Continentals. Attacking them rashly, he was driven back behind a ravine. The Second Maryland regiment, however, was broken by an attack of the second battalion of English guards, and two 6-pounders were taken. The First Maryland regiment and Colonel Washington’s cavalry charged the guards, drove them back in Confusion, and recaptured the guns. Then Lieutenant Macleod of the British artillery opened fire with two 3-pounders on friend and foe alike. Washington’s dragoons were checked, Webster advanced again and was supported by a part of Leslie’s division, and General Greene drew off his army, abandoning his artillery, whose horses had been shot.

The Hessians engaged in this battle were a detachment of chasseurs and the Regiment von Bose. This regiment was on the right of the British line. It was opposed throughout the action to the riflemen under Lee and Campbell, who attacked it with great determination, both in front and rear. In this Position the regiment behaved with great valor, and, at one time, relieved the first battalion of English guards, which had been thrown into confusion. A decisive share in the victory is claimed for the Hessian regiment by Eelking and Bancroft. This share can hardly be conceded to it, but the soldiers, and Lieutenant..colonei du Puy, who commanded them, deserved the favorable mention in despatches which they obtained from Lord Cornwallis.

The whole engagement lasted about two hours. The total loss of the British was five hundred and thirty-two, of whom eighty belonged to the Regiment von Bose.[Footnote: For Guildford Court-House, see Bancroft, vol. x. pp. 475-480; Eelling's “Hulfstruppen,” vol. ii. pp. 101—104; Marshall, vol. iv. pp. 368-379; Sparks’s “Correspondence,” vol. iii. p. 266; Tarleton, pp. 271—278 and (Lord Cornwallis’s official report) pp. 303—310; Stedman, vol. ii pp. 337—345; Lee’s “Memoirs,” pp. 274—286; Ewald’s “Belehrungen,” vol. ii. p. 135; vol. iii. p.322; MS. journal of the Regiment von Bose.] Cornwallis was so crippled by his victory that he turned away from the Virginian border and marched down to Wilmington to rest his army, leaving his severely wounded behind him.

Lord Cornwallis having retired to the coast, General Greene overran the states of North and South Carolina. Before the middle of September the Americans had lost three battles and conquered three provinces. Successively defeated at Camden, Ninety-six, and Eutaw Springs, Greene and the partisan leaders that cooperated with him took many smaller posts by siege, or storm, and caused the capitulation of Augusta, and the evacuation of Camden and Ninety-six. In the autumn of 1781 the British held no part of the three most southern states, except Savannah, Charleston, and Wilmington.

On the 10th of December, 1780, Benedict Arnold, now a British brigadier-general, sailed from New York at the head of about sixteen hundred men, including one hundred Hessian chasseurs under Captain Ewald. Arnold reached James River early in January, 1781. There was no one to oppose him but a small force of militia, under Baron Steuben. Arnold burned the town of Richmond, with its stores of tobacco, and then retreated to Portsmouth, at the mouth of the James. It was soon after this that the chasseurs gave another proof of their valor. On the igth of March, 1781, the American General Muhlenberg, with a party reckoned at five hundred men, advanced against the British line, scattered and partially captured a picket of chasseurs, and approached the position held by Captain Ewald. This was at first defended by a non-commissioned officer and sixteen men. The captain and nineteen more men hastened to assist them. The Americans had to advance over a narrow dyke, some thirty paces long, and on this they were crowded together. Every shot told in their ranks, and twentynine were killed or wounded. The chasseurs lost but two men, and Muhlenberg drew off his force. “On these occasions,” says Ewald, “we must screw the heels of our shoes firmly to the ground and not think of moving off, and we shall seldom find an adversary who will run over us in such a position.” Ewald was wounded in the knee in this skirmish. Eelking relates that Arnold came to see the captain after the fight. Ewald reproached the general for not reinforcing the chasseurs. Arnold answered that he had thought the position was lost. “So long as one chasseur lives,” cried the angry captain, “no — American shall come over the dyke.” Arnold, who still considered himself an Amen.. can, took this in bad part, and showed his pique by omitting to mention the conduct of the chasseurs in the orders of the day. Ewald complained of this to Arnold’s aid, and the general came to him the next day with apologies, and rectified the omission.[Footnote: MS. journal of the Jäger Corps; Ewald’s “Belehrungen,” vol. ii. p. 169; Eelking’s “HUlfstruppen,” vol. ii. pp. 107, 108.]

Meanwhile Lafayette, with twelve hundred Continentals, had been ordered to Virginia. The young general marched at once with a part of his force, leaving Wayne to follow with the remainder. Ten French ships of war were sent to co-operate with the marquis. These fell in with the English squadron, on the i6th of March, off the capes of Virginia. After an engagement, which lasted two hours, the French fleet sailed back to Newport and the English entered Chesapeake Bay. The defence of Virginia was thrown on the land forces exclusively, and these were unequal to the task.

On the 19th of March Major-general Phillips, the same who had been taken prisoner with Burgoyne at Saratoga, sailed from New York to assume command of the English forces in Virginia. He took with him a reinforcement of two thousand men, and nearly as many more followed him six weeks later. Soon after his arrival General Phillips sallied out from Portsmouth, went up the James River burning and plundering on both banks, carried off the negroes and shipped them to the West Indies, destroyed the magazines at Manchester, under the nose of Lafayette, who remained on the north side of the river, and on the gth of May took possession of Petersburg, where his army was to make a junction with that of Lord Cornwallis, advancing from Wilmington. Four days later General Phillips died of malignant fever, and Arnold was again in command of the army. On the 20th, however, Lord Cornwallis arrived at Petersburg, and the traitor was shortly afterwards sent back to New York.

Cornwallis left Petersburg on the 24th of May, crossed the James River twenty-five miles below Richmond, and on the first of June was at Cook’s Ford, on the North Anna River, near Hanover Court House. Thence he sent Tarleton on a raid to Charlottesville, where the Legislature of Virginia was in session. Tarleton scattered the legislature, and took a few of its members. Meanwhile Simcoe was sent to take or destroy some magazines and stores at Point of Fork, where the Rivanna and Fluvanna rivers unite to form the James. He found that the stores, which were under the guard of General Steuben, were on the south side of the James River. There was no ford, and Simcoe had but a few small boats. He, therefore, resorted to a stratagem. By drawing out his four hundred men in a long line, and half displaying and half concealing them, he succeeded in making Steuben believe that his command was the advanced guard of Cornwallis’s main army. Not reflecting that with only a few skiffs in which to cross the river a whole army was hardly more formidable than a detachment, Steuben retreated, leaving a part of the stores behind him. Twenty-four men were, thereupon, set across the river, and while half of them kept watch the others destroyed the stores without being disturbed.[Footnote: Ewald, vol. ii. pp. 194—199; Stedman, vol. ii. pp. 389, 390. Kapp says that the stores destroyed were of small value, and believes that Steuben acted wisely.—Steuben’s “Leben,” pp. 429—436. See, also, La. fayette’s “Mémoires,” vol. i. pp. 97, 150.]

Lafayette retreated as far north as the Rappahannock, where Wayne joined him with reinforcements. The marquis then made a rapid march to the southward and westward and placed himself between the British army and the stores in the western part of the state. He was still too weak, however, to risk a battle. Cornwallis did not advance against him, but on the 15th of June turned towards the seaboard. This gave Lafayette an apparent advantage. He followed Cornwallis on the march, but at a respectful distance. The army under Lafayette at the time numbered forty- five hundred men, of whom only one thousand five hundred and fifty were regulars.[Footnote: Johnston’s “Yorktown Campaign,” p. 55; Lafayette to Washington, June 28th, 1871, in “Mémoires de Lafayette,” vol. i. p. 150.]

But two engagements occurred during this return march. The first of them was on the 26th of June. A party under Simcoe and Ewald, forming the rear guard of the British army, was attacked, and in a measure surprised by a detachment of Wayne’s division. The British and Hessians were resting at noon not far from Williamsburg, when the Americans made a spirited attack upon them. The cavalry were soon mounted, however, and the chasseurs under arms, and the Americans were beaten off, with a loss on either side of thirty or forty men.[Footnote: Ewald’s “Belehrungen,” vol. iii. p. 474; Tarleton, pp. 301, 302; Johnston’s “Yorktown Campaign,” pp. 56, 190, with official return of the American loss.]

At Williamsburg Lord Cornwallis received orders to send back three thousand men to New York, which Clinton supposed to be threatened by the combined forces of France and the United States. For the purpose of carrying out this order, Cornwallis proceeded on his march to Portsmouth. On the 4th of July he left his camp at Williamsburg and marched to Jamestown, with the intention of crossing the James River. The rangers under Simcoe and the chasseurs under Ewald crossed the same night. A part of the baggage was taken over the next day. On the 6th of July Cornwallis, with the army, remained at Jamestown, and the general received intelligence that Lafayette was marching to attack him. This was what Cornwallis wished, as he had a good position and a much larger number of regular soldiers than Lafayette.

On the afternoon of the 6th of July Lafayette drew near, uncertain whether the main army of Lord Cornwallis was on the left bank of the James, or only the rear guard. The Americans came on cautiously. Wayne attacked with about five hundred men. The British pickets had received orders to make a stubborn resistance and then fall back. Encouraged by this, Wayne brought the rest of his brigade into action, having thus more than one thousand men in line. The remaining Continentals of the army formed a reserve. It seemed to Cornwallis that the moment to strike had come. His army was drawn up in two lines. The first consisted of about twenty-five hundred men. The second, in which was the Regiment von Bose, was about one thousand strong. Wayne and Lafayette discovered their error, and saw that it could best be redeemed by boldness. Wayne advanced with his brigade. This checked the British. The hostile lines halted about seventy yards apart, and a brisk fire was kept up for fifteen minutes. Then, as the British were beginning to outflank them, the Americans fell back. Two cannon, taken from the Brunswickers at Bennington, were left on the field, their horses having been shot. The loss of the Americans was reported at one hundred and thirty-nine, that of the British at seventyfive.[Footnote: For Green Spring, see Johnston’s “Yorktown Campaign,” pp. 60 et seq., 190; Bancroft, vol. x. p. 507; Eelking’s “Hulfstruppen,” vol ii. p. 114; Ewald’s “Belehrungen,” vol. ii. p. 332—335; Wayne to Washington, Sparks’s “Correspondence,” vol. iii. p. 347—350; Tarleton, pp. 353— 357; MS. journal of the Regiment von Bose. Also a letter from Ewald to Riedesel, Eelking’s “Riedesel,” vol. iii. p. 336.]

After arriving at Portsmouth, Cornwallis received counter-orders, and retained the whole of his army. He was to occupy and fortify Old Point Comfort and, if he considered it expedient, some other situation on the peninsula, suitable for a naval station. The engineers having reported adversely on Old Point Comfort, Cornwallis, in the first week in August, occupied Yorktown, and the small village of Gloucester, opposite to it. Here he soon collected his whole force, and went busily to work fortifying his position, while Lafayette waited and watched him.

Just at this time Washington was informed that the French fleet, under Count de Grasse, was preparing to assist in the operations near Chesapeake Bay. Preparations were quickly and secretly made to move the American and French armies from New York to Virginia. We have seen that on the 18th of August it was already reported in the city of New York that the allies were crossing the North River. There were so few boats that this operation lasted a week. Sir Henry Clinton, although warned of Washington’s design, was still under the impression that an attack on Staten Island might be intended. It was not until the 29th that he was undeceived. Leaving less than four thousand men under General Heath to guard the Highlands, Washington and Rochambeau were in full march against Cornwallis.

The allied army which was crossing New Jersey, and on which the fate of the war depended, was a very small one. It consisted of four thousand Frenchmen and two thousand Americans. Passing through Philadelphia, it arrived at Head of Elk on the 6th and 8th of September, 1781. Already the Count de Grasse had arrived in the Chesapeake with twenty-four ships of the line, carrying seventeen hundred guns and nineteen thousand seamen. Against him, on the 5th of September, came Admiral Graves, with an inferior force. The battle lasted two hours, and the English, though not decidedly beaten, were not in a condition to undertake anything more against the French. They sailed off to New York four days later, leaving de Grasse master of Chesapeake Bay.

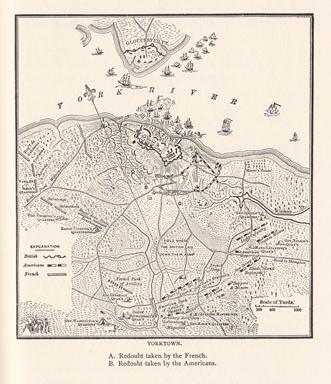

The Frenchmen and Americans who had come from New York were now brought down the bay, and joined with Lafayette’s corps and the French troops brought by de Grasse. The united army at Williamsburg on the 27th of September, 178r, consisted of about seven thousand Frenchmen, fifty-five hundred Continentals, and thirty-five hundred Virginian militia. In the ranks of the Continentals were companies from all the states north of the Carolinas. The English army at Yorktown numbered some seven thousand soldiers. Of these, not quite eleven hundred were subjects of the Margrave of Anspach-Bayreuth, rather more than eight hundred and fifty were subjects of the Landgrave of Hesse-Cassel, and the remainder, or about five thousand men, were subjects of the King of Great Britain, to whom all in this army had sworn obedience. About eight hundred marines fought on each side during the siege. The French fleet was not within range, but the English ships were actively engaged.

Yorktown was not a strong position, and was defended only by field-works. On the 30th of September, 1781, the British abandoned their outer line of defences, perhaps prematurely. On the night of the 6th of October the first parallel was made. On the afternoon of the 9th the parallel opened fire, and from that time to the end of the siege the cannonade was nearly continuous.

Almost the first fighting that occurred was a skirmish, on the Gloucester side of the river. Here were posted Simcoe’s rangers, Tarleton’s dragoons, Ewald’s chasseurs, and an English regiment. Opposed to them were more than a thousand Frenchmen under Choisy and de Lauzun, and twelve or fifteen hundred militia under General Weedoñ. Tarleton and Simcoe had discarded the use of carbines by their cavalry, and this aided in their discomfiture. On the morning of the 3d of October it was reported to Lauzun that there were English dragoons outside the works of Gloucester. Advancing to reconnoitre, he saw a pretty woman at the door of a small house by the roadside. Lauzun would not have been Lauzun if he had passed a pretty woman unquestioned. She informed him that Colonel Tarleton had just been at her house, and desired very much “to shake hands with the French duke.” “I assured her,” says Lauzun, “that I had come on purpose to give him that satisfaction. She pitied me much, thinking, I suppose, from experience, that it was impossible to resist Tarleton; the American troops were in the same case.”

A. Redoubt taken by the French.

B. Redoubt taken by the Americans.

Presently the French and English dragoons met. Tarleton raised his pistol and approached Lauzun. A single combat was imminent, when Tarleton’s horse fell. The English dragoons covered the escape of their colonel, but his horse was taken by Lauzun.[Footnote: “Mémoires du Duc de Lauzun,” p. 245; Ewald’s “Belehrungen,” vol. ii. p. 391; Tarleton, pp. 376—378; Lee’s “Memoirs,” pp. 496—498; Rochambeau’s “Mémoires,” pp. 291, 292.]

The 10th of October was marked by a deed of valor. Major Cochrane had left New York in a small vessel with despatches for Lord Cornwallis. He arrived at Chesapeake Bay in broad daylight, ran the gantlet of the French fleet, which fired briskly at him, and reached Yorktown in safety. This brave man had, however, seen the last of his good fortune. Two days after his arrival he pointed a gun with his own hands. As he looked over the parapet to see the effect of his shot, his head was carried off by a cannon-ball. Lord Cornwallis was standing by his side, and narrowly escaped sharing his fate.[Footnote: Ewald’s “Belehrungen,” vol. i. p. 11; Johnston’s “Yorktown Campaign,” p. 138, quoting a statement by Captain Mure in a letter published in appendix to vol. vii. of Lord Mahon’s “History of England.”]

On the night of the 11th of October the second parallel was opened. Two redoubts, facing the right wing of the allied position, were so placed as to interfere with this parallel. It was necessary to take them, The work of storming the larger one was intrusted to the French. The redoubt was manned partly by Germans. The French, under command of the Baron de Vioménil, were discovered and challenged at one hundred and twenty paces from the redoubt. Some time was spent in making an opening in the abatis. When this was passed the work was stormed. Ninety-two Frenchmen were killed or wounded in the attack. The loss of the enemy was fifteen killed and fifty prisoners. The Americans were equally successful in taking the smaller redoubt, and, as they were less delayed by the abatis, their success was more rapid. Nine men of their column were killed and thirty-one wounded, including five officers.

Early in the morning of the 16th of October a sortie was made against the second parallel. For a few moments it was successful, and several cannon were spiked, but the British were presently driven back by a charge of the French grenadiers, and the cannon were bored out within a few hours. On the following night Cornwallis made an attempt to take his army across the York River, with the intention of trying to get off into Virginia.[Footnote: See this plan discussed at length, Tarleton, pp. 379—385; and in Lee’s “Memoirs,” pp. 503—506.] A violent storm of wind and rain, which drove all his boats down the river, prevented him from carrying out this design, and such of the troops as had already crossed to Gloucester were brought back the next morning, leaving only the regular garrison of that place.[Footnote: Cornwallis’s report to Clinton, in Johnston’s “Yorktown Campaign,” p. 181. There were one hundred and forty.two Hessians killed and wounded at Yorktown (Knyphausen to the Landgrave, November 6th, 1781); this does not include the chasseurs at Gloucester, nor the Anspachers.]

The British artillery was now completely silenced, and Cornwallis saw that he could hold out no longer. On the 17th of October, 1781, negotiations were opened, and on the igth the capitulation was signed, the terms being substantially those accorded to General Lincoln at Charleston in the previous year. On the afternoon of the same day the British and Germans marched out of their intrenchments with cased colors, and with their bands playing an old English tune, “The World Turned Upside Down.”

[ The Hessians In The Revolution ]